The notation of musical instructions for performance has existed for thousands of years, going back to cuneiform tablets in Sumer. I cannot tell you how that ancient composer’s work was intended to be interpreted, nor how those performing it approached these instructions, but we still understand this concept today. Performers rehearse to convert the composer’s instructions into sound. While there is room for interpretation in many pieces, the goal is to recreate the composer’s vision. Now, with the great advances that have been made in digital music, composers have access to unprecedented levels of control of the finished sound, and it can be indistinguishable from a real human performance. This level of control over sound is a positive, something to be celebrated, but it can reduce the necessity of the human musician. Many film scores are using a blend of live performers and digital ones; some have no live performers at all! Where is the musician’s place in this world?

Our Robot Overlords and the Value of Consistency

Digital music production gives the composer complete control over their pieces, and every time the piece is played, it will always sound just as the composer intended. This is a great asset. There is no need for multiple takes when recording, no misinterpretations by a soloist, no trumpet players ignoring the mezzo in mezzo forte. Detailed sheet music can be sequenced, almost like code being compiled, but the output is the finished piece of music instead of software. There are already programs that can scan physical scores and make them ready too be converted into files. We are not far from the ability to download sheet music in a PDF and have to be computer sing it to us. With precise instructions, composers can haunted guarantee their music will performed as they envisioned.

It is not just in performance that computers are catching up to human levels; computers are capable of generating music as well. It can be as simple as generating random sounds, or as complicated as using a neural network to compose pieces in the style the user chooses. These capabilities will only continue to advance. We might even see a film score composed and performed by an AI. There is great value to having a piece, or even all pieces, performed at a consistent level, and as digital music creation and performance continues to advance, there will be little need for the human element in those arenas.

The Human Element and the Value of Inconsistency

Be it in reference to a Mahler symphony or Bruce Springsteen, “You’ve got to see it live!” is often said about music. Part of what makes a live rock show great is how it is different from the recording, be it longer solos, transitions, or maybe it is just louder. Seeing musicians perform art music live has similar benefits. Here the musician is able to insert themselves into the composer’s instructions, turning a set of programmed instructions into something more.

Humans also differ from machines in another way: humans mess up. Errors are made; The symphony starts playing the piano concerto and it’s not the one the performer prepared, Wrong notes are played, rests are miscounted. Some of these mistakes lead to great stories or new ideas. Other ones just sound bad, but are often quickly forgotten. The human musician is able to play a piece in a different way that the composer intended, and they are able to mess up.

Humans also bring with them their experiences. The music they grew up listening to, the memories associated with certain pieces, these impact how humans see things. While musical notation goes back far into antiquity, music has been performed without instructions even further, and the oral tradition of music comes with its own trappings. One example is the blues. Not only its origins, but how it spread and was taught. There are many examples of successful musicians who have no classical training, or do not learn how to read music until after they have been playing and performing. All of these experiences give humans a unique view and their own Internal Musical Language.

Performing Art Music in the Information Age

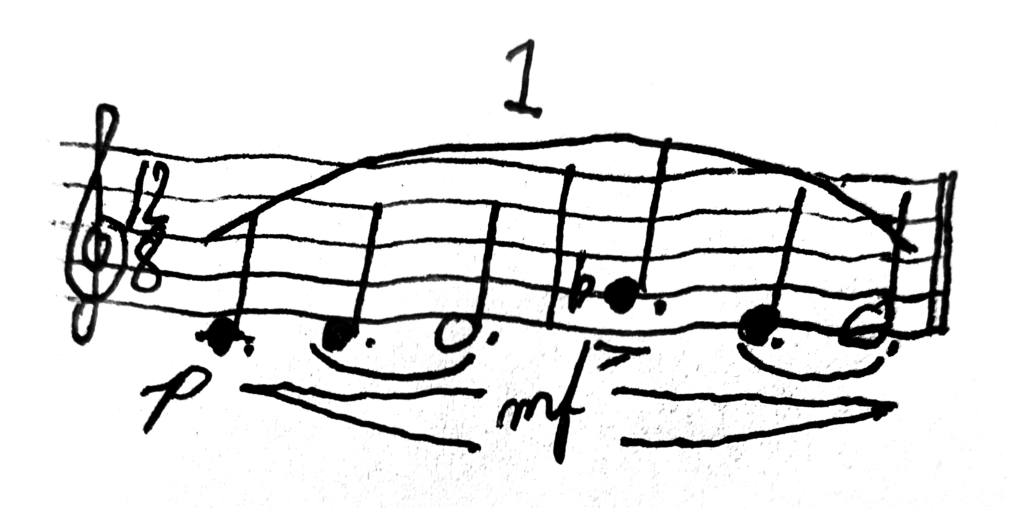

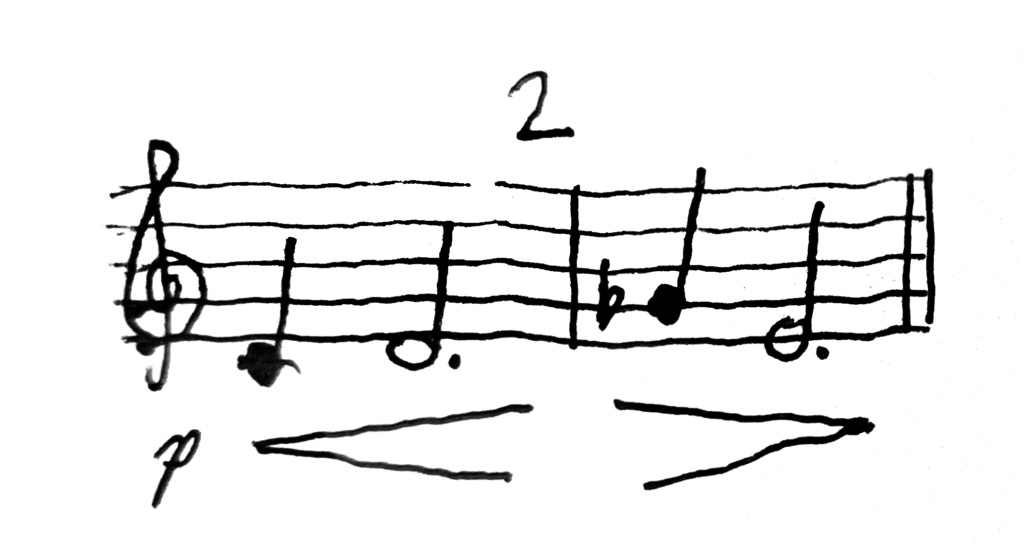

Sheet music is like code. It can be an explicit set of instructions that have an intended output. If a composer wants a piece to always sound the same it would make the most sense to create it digitally. It is a matter of who the intended audience is. It you are writing for the listener, you want consistency. But if your audience is the musician, what can you do differently? The musician can interpret a piece of sheet music differently than a computer, but what about interpreting things the computer cannot? This can be achieved in a variety of ways. An easy place to begin is to put the minimum amount of instructions into a piece, or set the music in a more abstract way. (Figures 1-3). This concept can be taken quite far, even to the point where the instructions no longer resemble sheet music (Fig. 4). Leave space for the musician to interact with. Pieces like this are a conversation between the composer and the performer. Pieces like Variables may not be aesthetically pleasing to the ear, but that is not it’s purpose. Pieces like that serve as etudes in musicianship, they don’t ever need to be performed in front of an audience, the piece is intended for the musician. One of the goals of such works is to help the performer get out of the instructions on the page and into the music, and allow them to speak it through the lens of their Internal Musical Language. Musicians can use these pieces as practice tools, or perform them.